Via Jonathan Clements I have discovered that the magazine Renditions, published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, has produced a bumper issue of Chinese SF in translation. There are stories by Liu Cixin, Han Song, La La, Zhao Haihong, Chi Hui and Xia Jia, amongst others. They look to be all new translations too, in that none of the story titles are familiar to me. Thank goodness we added that rule about picking up stories we missed from the previous year to the translation awards. These can go on next year’s list. It looks like the cost would be US$39.90 airmail or US$33.90 surface mail.

Via Jonathan Clements I have discovered that the magazine Renditions, published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, has produced a bumper issue of Chinese SF in translation. There are stories by Liu Cixin, Han Song, La La, Zhao Haihong, Chi Hui and Xia Jia, amongst others. They look to be all new translations too, in that none of the story titles are familiar to me. Thank goodness we added that rule about picking up stories we missed from the previous year to the translation awards. These can go on next year’s list. It looks like the cost would be US$39.90 airmail or US$33.90 surface mail.

Science Fiction

Vandana Singh on 2312

As you doubtless know by now, I’m quite fond of Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312. However, I’m not without reservations, as I hope my review makes clear. Today I found some of those reservations writ large by Vandana Singh. I can see exactly where she’s coming from on this, and I think it’s a valid view to have of the book. In my defense, I note that I disliked Swan so intensely that I got the impression that Stan was using her to satirize the naive and lazy nature of Internet activism, rather than inadvertently revealing his own views of foreign cultures. I still cringe when I think of what I have come to think of as the “animal droppings” episode, though. Thanks Vandana, that was a useful perspective.

Marie Brennan on Grimdark

There has been a lot of discussion of the subject of “Grimdark” fantasy around the blogosphere of late. Mostly I’m ignoring it, because I know how such things tend to degenerate, but I did want to point you to this fine essay at the SF&F Novelists blog. It is by Marie Brennan, and it blames the whole thing on the infamous Thomas Bowdler. I find Brennan’s argument quite compelling.

Small Blue Planet, Episode 3: Brazil

It lives! Karen Burnham has just posted the latest episode of Small Blue Planet to the Locus Roundtable blog. You can find it here. Many thanks to Fábio Fernandes and Jacques Barcia for being such great guests. I particularly enjoyed the tale of author Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro who maintained a female alter-ego for 6 years, producing the Xochiquetzal stories along the way. So, break out the Caipirinhas and head on over to Locus for some fine entertainment.

Meanwhile I am lining up the guests for the next three episodes. In the next few months we will be visiting France, Israel and The Philippines.

Zambian Space Program on Kickstarter

Yes, really. I love the Afronauts. And now, with any luck, there will be a film. You can back it here.

India and Brazil

Today I spotted an academic paper on this history of science fiction written in Hindi. You can read it here. It is great to know that people were writing SF in Hindi at the end of the 19th Century.

And talking of SF that I can’t read, this evening I recorded episode 3 of Small Blue Planet. It features Brazil, and the guests are Fábio Fernandes & Jacques Barcia. Karen Burnham should have it online in a week or so. We talked about a whole range of issues, from Brazilian steampunk to a male author who created a female alter-ego and kept up the masquerade for 6 years, and of course caipirinhas.

Trans, Bodies and Art

Over the past few days I have encountered several references to the use of trans people in art. Firstly there is this article, referencing the LGBT History exhibition, which appeared on Unmaking Things, a blog that is a joint production of the Royal College of Art and the Victoria & Albert Museum. We’ve also had a request, following on from the exhibition, to find trans people who are willing to be photographed for an art project. And finally, some asked on Twitter if I thought it was reasonable to claim to have gained an understanding of trans people through reading science fiction.

What these all have in common is that they involve the representation of trans people in art, probably by cis people. In her blog post, Lauren Fried notes that in the exhibition, “There is very little imagery which pertains to the (re)design of bodies here; instead, the histories of these bodies are referred to through objects and archival documentary sources.†This was very deliberate on our part and Fried, though her academic interest is in the design of bodies, understands why we did it. (I’ve since corresponded with her on Facebook.)

All too often, images of trans people, both factual and artistic, are intended to other the subjects. We get the notorious “before and after†shots that the newspapers are so fond of running (and that trans celebrities are automatically asked for, even when an article featuring them has nothing to do with their transition or history). And we get gender-bending art displays that either revel in androgyny or present “you can’t tell†images.

Of course there is a place for such things. The exhibition does contain a portrait of a trans woman, local theatre director, Martine Shackerley-Bennett, who allowed her artist friend, Penny Clark, to chronicle her transition. You can learn more about the work Penny did in this YouTube clip.

There is also a long and honorable history of performers such as David Bowie, Boy George, Tilda Swinton and Andrej Pejić who delight in presenting an androgynous appearance. That is their right, and the questioning of gender boundaries that results from their actions is to be welcomed as it has done a great deal to advance public acceptance of trans folk.

Where problems arise is when people start with the gender-bending image and conclude, “this is what trans people are.†As I hope regular readers will be aware by now, the truth is much more complicated. While there are many trans people who would love to be as famous, good-looking and as brain-exploding as Swinton or Pejić, there are many who do not. Very few want to be the subject of “freak show†imagery.

So how does this fit into learning about trans people from SF? Well, if you’ve read my essay on the subject you’ll know that most 20th Century SF featuring trans people was written by cis people who seemed to have very little idea what actual trans people were like. It also tended to make the trans folk “issue charactersâ€, by which I mean that their otherness was the significant thing about them, the reason why they were in the story. Respectful or not, it tended to be the literary equivalent of the freak show image.

The other thing about 20th Century SF is that it often features gender transition as a choice rather than as something the characters need to do in order to be themselves. The assumption is that future technology allows such essentially cosmetic surgery, and so people will opt for it. Iain Banks, to his credit, has always acknowledged that such choices are predicated on a society that has achieved gender equality. Few people would choose to become a member of an oppressed group in society. In our current society, where women are still second class citizens, and trans people are often barely accepted as human, the idea that transition is a lifestyle choice is deeply offensive to many who undergo it.

So does reading 20th Century SF actually help you gain an understanding of trans people? From one point of view, clearly not. I’ve had earnest people tell me that they know all about folk like me because they have read John Varley’s Steel Beach. This makes me want to put my head in my hands and weep. If that’s what you get out of your reading then you are in deep trouble.

On the other hand, what SF has always done is usualize the idea of gender transition. (Yes, “usualize†is a made up word. That’s because the word commonly used in a sentence like that would be “normalizeâ€, and “normal†has all sorts of connotations beyond the mathematical.)

What I mean by this is that if you read SF (and to a lesser extent fantasy) then the idea that someone might change their gender is not strange and frightening. SF readers are accustomed to reading about things that might not (yet) be real, whereas those who do not read SF often excuse themselves by saying that they can’t accept things that are not real, even in a work of fiction (which is, by definition, unreal). If you can’t accept the possibility of a changing world in fiction, the chances are you won’t be too keen on actual changes in the real world.

So I do think there is a way in which reading SF can help people to accept trans people. Of course it isn’t foolproof. While there are some people for who reading SF as made them eager and willing to encounter aliens, there are others who feel it has taught them that the only good alien is a dead alien. I’m also aware that there are SF fans who are perfectly OK reading about people with green skin and tentacles, but can’t cope with ordinary humans who have brown skin, or breasts. Art does not affect all people in the same way. However, I can see how reading SF may have helped people to be more understanding about difference. Whether those people would have been as understanding without it, I can’t say, and neither can they. If they want to credit their reading as being formative, I’m happy to let them.

Free Islamic SF

Via Farah Mendlesohn I’ve been made aware of an anthology of science fiction stories with Muslim characters and Islamic themes. A Mosque Among the Stars was first published in 2007 and is now available as a free PDF. The book is edited by Muhammad Aurangzeb Ahmad and Ahmed A. Khan, and contains stories by Lucius Shepard, Camile Alexa, Jetse de Vries and others. You can get a copy here.

New Fiction Magazines

Yes, yes, well all know that short fiction is dead, right? That’s obviously why I have heard of two new magazines being launched just this week. And it is only Tuesday.

Actually the first one isn’t strictly short fiction, because what it will do is serialize longer stories. That, of course, is how SF novels always used to be published, back in the glory days of the US magazines. Well done Tony Ballantyne for thinking of resurrecting it. The magazine is called Aethernet, and Juliet, who has a story in it, talks more about it here.

The other one is genuine short fiction. It is called Crowded, and originates from Australia. They tell me that they pay professional rates, and they are open to submissions. Further details are available here.

Here’s hoping both do well.

Living In The Future

OK, so we have flying cars and jetpacks (if we can afford them, and get the necessary operating licenses), but did I really expect to see an Observer editorial warning abut the dangers of killer robots? Color me gobsmacked.

Magnus, where are you when we need you?

Tolkien Lecture Online

The lecture on fantasy literature that Kij Johnson gave in Oxford last month is now available online, both as a PDF (complete with Kij’s scribble where she ad-libed on the day), and as a podcast. You can find both here.

An Essential World SF Reference Work

Today I received a review copy of World SF in Translation, a bibliography of around 3,500 science fiction novels and stories that have been translated into English. It covers 1165 authors from 54 different countries. The author is Finnish scholar, Jari Koponen, and the book’s brief preface is printed in Finnish, Swedish and English. The vast majority of the content, however, is in English because it is titles of books and stories. The book is readable by anyone who can read English.

Sadly, having come from a Finnish publisher, Avain, the book isn’t easily available. It is also quite expensive, being a specialist work. It looks like you can buy copies here. Possibly someone from Finland will know of a better source. Anyway, it is an amazing resource, and one that deserves to be more widely known.

Also, Best Related Work. It will be on my ballot.

Small Blue Planet Update

Yesterday Karen Burnham and I recorded episode 2 of Small Blue Planet, with special guests Ken Liu and Chen Qiufan. It will be a week or two before it goes online because there is a substantial time lag on Skype calls to Beijing and Karen needs to clean up the recording to get rid of all the silent pauses. It was, however, great fun to do,and I hope you’ll enjoy it as much as I did when it finally airs. Ken had some really interesting things to say about translating from Chinese, and we discussed lots of interesting Chinese writers.

In the meantime, of course, episode 1, on Finland, is available from the Locus Roundtable blog. I’ve had quite a bit of feedback from listeners in the Nordic countries, but nothing much from elsewhere. This is a country bidding for a Worldcon, folks. You should be finding out about them.

Small Blue Planet, Episode 1: Finland

It is probably dreadful timing for me to be mentioning two podcasts on the same day, but Karen Burnham put the first episode of Small Blue Planet online last night to I need to point you at it. As you hopefully know by now, this show will feature me talking to people from the SF&F communities in various countries around the world. For the first episode my guests are Jukka Halme and Marianna Leikomaa from Finland. They are both good friends, so the chemistry was excellent on the show. I hope you enjoy it.

And yes, we do talk about the Helsinki Worldcon Bid.

On Sunday I’ll be recording Episode 2 with Ken Liu and Stanley Chan (Chen Qiufan) who will be telling me all about science fiction and fantasy in China. If you have things you want me to ask them, let me know.

Huge thanks to Locus for agreeing to host these podcasts. Hopefully this will do wonders for listener figures.

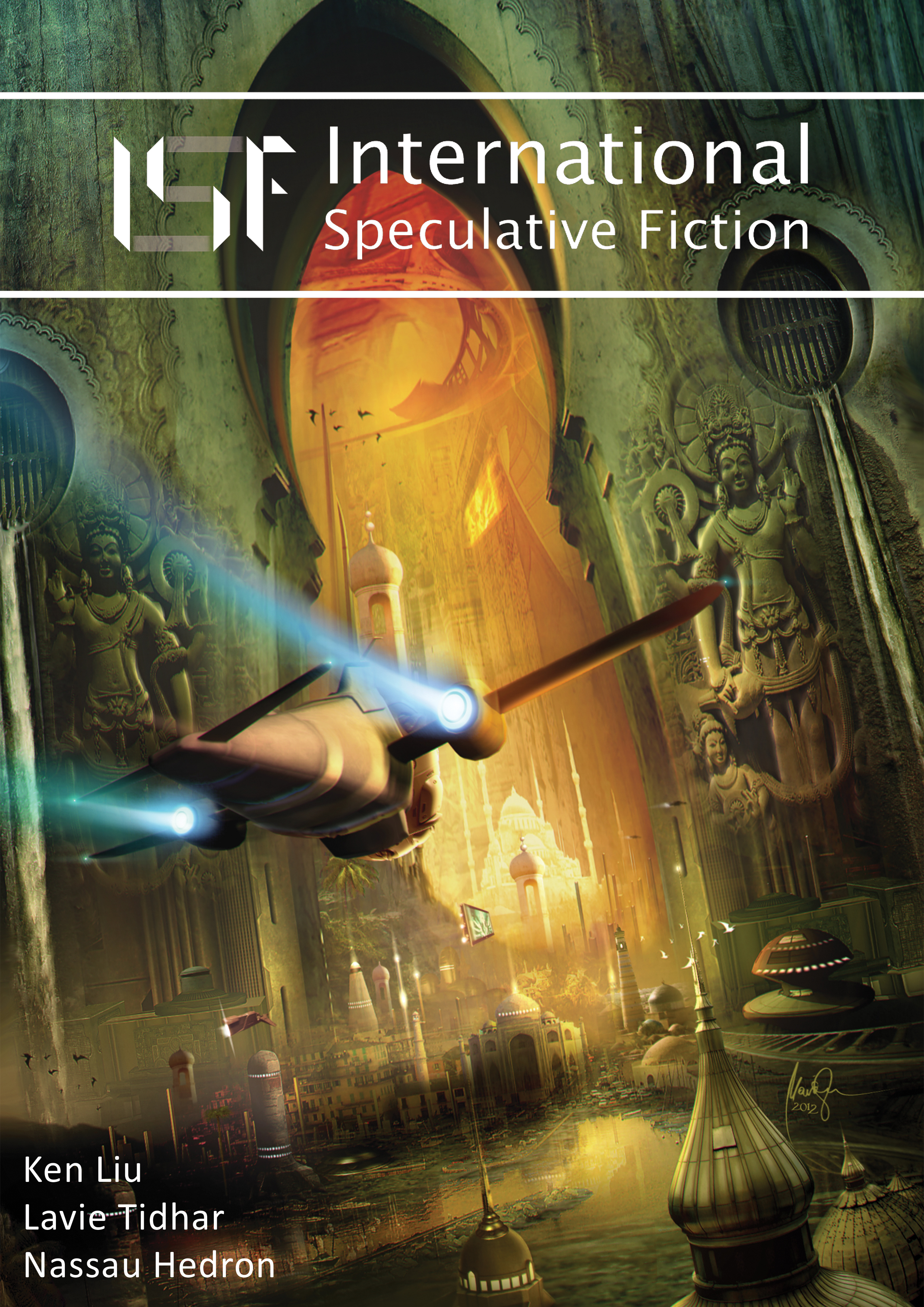

ISF #3 Is Live

Issue #3 of International Speculative Fiction went live last night. As usual it is available as a free download. It has fiction from around the world. It has book reviews from my Aussie friend Sean Wright. And it has Jess Nevins’ article, “Pulp Scifi under German, Russian, Japanese and Spanish Totalitarism”. What are you waiting for? Go, go, go!

Back From The Dead: Amazing Stories

For some time now Steve Davidson has been working on reviving the venerable science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories. This week it launched a new website which looks very slick and is full of content. They don’t appear to be buying fiction yet, but it is good to see something online and fingers crossed it will grow from here.

New Podcast – Small Blue Planet

Yes, I know, the last thing I should be doing right now is starting a new project. Don’t I have enough to do already? I thought of that myself. But this was such a good idea, so I’m doing it.

I blame Karen Lord. I was chatting on email to her and Karen Burnham, mainly about their awesome SF Crossing the Gulf podcast. Ms. Lord said something to the effect that someone should do a podcast about translation. Oh, I thought, that had better be me. Fortunately Ms. Burnham thought it was a good idea too, and offered to produce it and get it online. All I have to do is find the guests and interview them. And that, I can assure you, will be a pleasure.

The podcast will be called Small Blue Planet. The basic idea is that each month I will have two guests on the show, spotlighting a different country each episode. The guests will mostly come from countries where English is not the dominant language. They will be readers, writers and translators of science fiction and fantasy. I’ll get them to talk about the SF&F scene in their country, and also about their language. We’ll talk about conventions and fanzines, about their local writers, about what English-speaking writers are popular in their country, and about the pros and cons of their language and culture for writing SF&F.

Karen will be putting the finished podcasts up on the Locus Roundtable blog. And hopefully she’ll ask a few questions of her own during the discussion.

There was no question which country I should start with. Our guests for January will be Jukka Halme and Marianna Leikomaa. They have both chaired successful Finncons. Jukka is one of Finland’s foremost SF&F critics, and Marianna is an experienced translator. And yes, we will talk a bit about that Finnish Worldcon bid. We’ll also talk about Johanna Sinisalo, Hannu Rajaniemi, and many wonderful writers that you are probably not yet familiar with.

We will celebrate the Chinese New Year in February by talking to Ken Liu and Stanley Chan (Chen Qiufan). Ken is the first person ever to win the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy Award for the same story (“The Paper Menagerieâ€). Together they won the 2012 SF&F Translation Award: Short Form for Ken’s translation of Stanley’s “The Fish of Lijiang†(Clarkesworld #59). Stanley works for Google in Beijing and has won several awards for his fiction in China.

In March we move on to another emerging economic power: Brazil. Our guests will be Fábio Fernandes and Jacques Barcia. You probably know Fábio from his articles on SF Signal and other places. You may not know that he is the Brazilian Portuguese translator for Neuromancer, Snow Crash, A Clockwork Orange and many other fine books. Jacques is an author and musician. Several of his stories have appeared in English.

That’s as far as the planning goes right now. In April and May I’m likely to be at conventions in Europe and hope to do some live recordings there. I also have plans to reach out to Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Occasionally we’ll visit countries that we might think of as English-speaking, but which have a wide range of local languages as well; places such as India and South Africa. Some of you are probably thinking that I’ll be pestering you soon, and you may well be right. Email if you are keen.

The plan is to try to do one episode a month. However, I’m not going to advertise a precise schedule. It all depends on when our guests are available. Also Karen has her job at NASA and a small son to worry about, and I have a publishing company and bookstore to run. Don’t worry though, we’ll both blog and tweet about new episodes as they become available.

I am so excited about this. Initially it will give me a chance to promote the work of some talented friends, and longer term I’m hoping I’ll make new friends in countries I know little about. I know I’ll learn a lot, and I hope you will too.

The Tolkien Lecture

As Kij Johnson said in her opening remarks, the great thing about an inaugural lecture is that there is no precedent, nothing to constrain what you can and can’t talk about. Even the title isn’t much of a straightjacket as the lecture series is not supposed to be about Tolkien, only in honor of him. Thus Kij was free to talk about her own approach to fantasy. Mostly the great man whose spirit we were invoking was absent from the narrative, but having had time to think about what Kij said, I have come to the conclusion that it was very much a lecture that engaged with Tolkien, even as it barely mentioned him.

Kij based the lecture on work that she has done with her students at the University of Kansas, and that in turn is based on Brian Attebery’s work on categorizing approaches to writing fantasy (e.g. in Strategies of Fantasy). This area has since been addressed by others, for example Farah Mendlesohn in Rhetorics of Fantasy. During the lecture I found myself wondering where discussion might have gone had Farah been there (I talked to Kij later and she has good practical reasons for her use of Attebery). Adam Roberts didn’t turn up either — the snow kept a lot of people away — so he wasn’t around to pour scorn on the whole idea of taxonomies, as he is wont to do.

I have a great deal of sympathy with Adam on this point. The trouble with taxonomies is that the people who design them tend to get obsessed with proving that their own scheme is correct and complete, forcing them into ever more bizarre contortions in order to shoehorn every work into the boxes they have created, while writers like Mike Harrison, Kelly Link, China Miéville and Kij herself merrily run around blowing those boxes up.

The usefulness of taxonomy is the way in which it allows us to examine how pieces of fiction work, and that’s how Kij was using it with her students. For me, the most interesting part of the lecture came when she was explaining how her students found ways in which works, particularly her own, did not fit on a simple axis between mimetic (realistic) and fantastic fiction.

Kij’s own fiction is remarkable in the manner in which she drags us into the story with carefully crafted detail (see the following post on the writing masterclass for more discussion of this). And yet she often does this in settings which are totally bizarre. There’s no way in which stories like “Poniesâ€, “Mantis Wives†and “Spar†can be said to be in the real world, even when they are so obviously about it. During the lecture, Kij made a remark about how fantasy is inherently meta-fictional because its very unreality informs you that you must be reading a story. I flagged this as important at the time, though it took a night’s sleep to work out why.

Of course there is a sense in which all fiction is unreal. That can be a very useful point to make if your purpose is annoying idiot LitFic fans who argue that SF&F are “no good†because they are “not realâ€. Here, however, it misses the context. As we are discussing literary theory, the remark has to be understood within the traditional theoretical definition of fantasy (as developed by Todorov, and subsequent writers) as being fiction about that which cannot happen, as opposed to that which could be a report of real events (mimetic fiction) and that which might plausibly occur in the future, but cannot happen now (science fiction). Also one’s position on the axis from the mimetic to the fantastic is very much dependent on the relationship between the reader and the text. It is a matter of suspension of disbelief.

And suddenly we are back with Tolkien. In his famous essay, “On Fairy-Storiesâ€, Tolkien argued that it was the duty of the fantasy writer to create a believable world as the setting for the fiction. That’s why the world of Middle Earth is so incredibly detailed. Kij does not do this. Her stories have incredibly realistic levels of detail, and yet their settings are often so fantastic that their unreality is beyond doubt. The reader is forced to confront the unreality of the setting, and ask herself why the author has done this.

Tolkien insists that successful subcreation, and consequent suspension of disbelief, is required when writing fantastic fiction:

The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside.

However, in doing so he is casting aside the whole of meta-fiction, the wonderful, knowing nod-and-wink to the audience that we have become so familiar with over the years since The Lord of the Rings was written. Meta-fiction relies for its effect on the fact that both writer and reader are aware that a story is being told. There are all sorts of reasons why a writer might choose this style of work, but in Kij’s case I think it is primarily to draw attention to the deeper layers of meaning within the story.

Tolkien famously insists that The Lord of the Rings is not allegory, and he’s right. There is no sense in which, for example, one character stands in for someone else, in the way that Aslan stands in for Jesus in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe. That does not mean that Tolkien’s novel is devoid of meaning. It is simply that the meaning is more subtly expressed, buried beneath layers of plot and character development. Most people now accept that The Lord of the Rings was influenced by factors such as Tolkien’s experiences in WWI, and by the industrialization of England, but I am sure that you can still find reviews that claim such statements are “reading things into the book that are not there†(a phrase that always causes me to cringe).

It is perfectly possible to write a simple, mimetic story about, say, failed relationships. However, fantastic fiction has a long and honorable tradition of being used to address an issue in ways that encourages the reader to think more deeply about it, by divorcing it from actual events. My usual example here is the way that Juliet McKenna uses fantasy to discuss political issues while side-stepping the emotionally-charged link to real world events that would skew the way that readers approach the book.

Unfortunately, the further removed from reality your novel, the less obvious your subtle buried connection to the real world becomes. Readers, many of whom only want comfort or escape, may fail to see it (and get quite angry when some smart-arse critic such as myself points it out). I don’t know why Kij writes the way that she does, but I’m guessing that the purpose of this grabbing of the reader by the throat and forcing her to confront the unreality of the story is a tactic to get people to think. We are invited to ask, “why is she telling me this?†“What point is she trying to get across?†“What does the author want me to take away from this?â€

I guess that there will always be people who think that “Spar†is just a cute tale about a human woman and an amoeboid alien having lots of sex, or that “Mantis Wives†is just a story of every-day creative cannibalism amongst insects. There will also be people who don’t want any deeper meaning to their reading. This, however, is an essay about literary theory, and that would probably not exist if all readers were like that. For the rest of us, the message of the lecture is that there is more than one way to do fantasy. Tolkien pretty much invented one very successful approach. Kij happens to be using an approach in which detailed subcreation has a part, but in which jolting the reader out of the secondary world is not just allowed, but essential to the intent of the author.

I’m not sure what Professor Tolkien would have made of all this. I rather suspect that he would have been dismissive of both Modernism and Postmodernism. But literature would be a boring place if Tolkien’s approach to fantasy was the one and only technique that was allowed. A series of lectures on fantasy literature should explore other approaches, and contrast them with the way that Tolkien worked. That’s exactly what Kij did (even if you have to peer below the surface of the lecture to see it).

On Shout Out: #TransDocFail, Doctor Who And Me

Last night’s episode of Shout Out is now available online. It includes Nathan and I talking about #TransDocFail, and a news report about a group of gay Doctor Who fans. That all starts around half way through, but there’s more mention of #TransDocFail and Julie Burchill earlier in the show. You can listen here. (If you come to this link more than a year after I posted it, you’ll need to scroll down to the January 17th episode.)

I could have done a lot better on the show. There were some key points I didn’t manage to get across. Practice. I need practice. But it is good to have these things out there.

New From ISF

Roberto Mendes has been very busy, and I have been very remiss in not tweeting about it. Issue #2 of International Speculative Fiction came out just before Winterval (well, during it, as my thoroughly pagan holiday begins with the equinox). I put the email to one side then, and forgot about it. I should not have done, as the issue contains, amongst other things, fiction by Ken Liu and Lavie Tidhar, plus and interview with Rachel Haywood Ferreira. And it is free. Get it here.

Issue #3 should be with us fairly soon. The table of contents is available here, and the thing I’m really interested in is “Pulp Scifi under German, Russian, Japanese and Spanish Totalitarism” by Jess Nevins. How Jess finds out about all this stuff I do not know, but he’s always a fascinating read.