Over the last few days I have watched a 3-part series on BBC4 called The Story of Women and Art. Structurally it follows a pattern dating all the way back to Kenneth Clark’s classic Civilisation: an academic with a mildly eccentric presentation style takes us on a tour of great Works of Art and enthuses over them. It is a while since I watched Lord Clark’s magnum opus, but I’d be prepared to bet that most, if not all, episodes go by without mentioning a single woman artist. Amanda Vickery has set out to put the record straight, by rescuing great art by women from obscurity (frequently back-room storage areas in museums and galleries) and putting it back on display, at least on our TV screens.

Unlike novel-writing, which has always been seen as a domestic activity, the creation of Art — by which I mean primarily painting and sculpture — has, for most of history, been the domain of men. Indeed, in much the same way as certain types of writing — most obviously romance — have been deemed “women’s work” and therefore of lesser value, so certain types of artistic activity — paper-cutting, embroidery, etc. — have been deliberately excluded from The Academy because they are the preserve of women.

I suspect that there is a correlation with fantasy literature here. According to Vickery, the highest form of Art is deemed to be History Painting; that is scenes from history, classical mythology or the Bible. Of this, War Painting is a particularly valued sub-genre. Interestingly, women artists flourished in The Netherlands in the 17th Century specifically because the fashion for art moved from dramatic scenes of human passion to the still life. Women were deemed incapable of producing war painting due to their lack of participation in war (cue Kameron Hurley rant). More damningly, however, History Painting, and associated sculptures, tended to emphasize the use of nudes, after the style of Greece & Rome. It would have been improper for a woman artist to study the male body in such a way as to be able to render realistic nudes, and if she did manage to do so that would be taken of proof of her sluttish nature. Women artists were therefore doomed either way.

Nevertheless, many bold women did manage to make their way in the arts, despite all of the barriers placed in their way. I’d like to highlight just a few.

Artemisia Gentileschi lived in Italy in the 17th Century and was adept at mythological paintings. She produced this (Susanna and the Elders) when she was just seventeen.

Later in life she joined her father at the court of Charles I in London where she helped him produce this ceiling at Malborough House in Greenwich. It is titled “An Allegory of Peace and the Arts under the English Crown”. No wonder Charles got his head chopped off if he gave out pompous commissions like that.

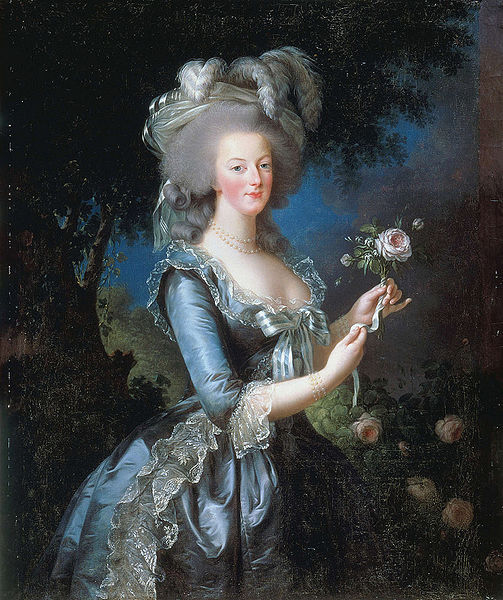

Moving into the 18th Century, I was surprised to discover that Marie Antoinette was a great patron of women artists. This portrait is by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun. The dress is probably one of many designed for her by the founding mother of the French fashion industry, Rose Bertin.

Sadly the killjoys of the Revolution did not approve of women taking up artistic pursuits, except perhaps knitting.

Finally, here’s the finest war artist of the British Empire. Every British schoolboy knows this picture. I suspect that very few know that it was painted by Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler; or that she actually stood in front of a Scots Greys cavalry charge to get a proper sense of what it should look like.

All in all it was a fascinating little series, if a little depressing in that it showed that the problems women writers have in getting recognized are if anything less than those faced by women artists.